On the death of criticism, the laundering of prestige, and why no one is telling the real stories

I professed I would not engage in the continued, exhausting critique of the art world because, frankly, it did nothing. It may have been an anchor of solace for someone else participating in a system that drains them of humanity and strips transgression out of a practice, which is the only redeeming quality of contemporary art.

Unfortunately, with fascism as the foreground and many galleries, museums, and figures acting as accomplices in this dystopian reality, there’s not much to write about.

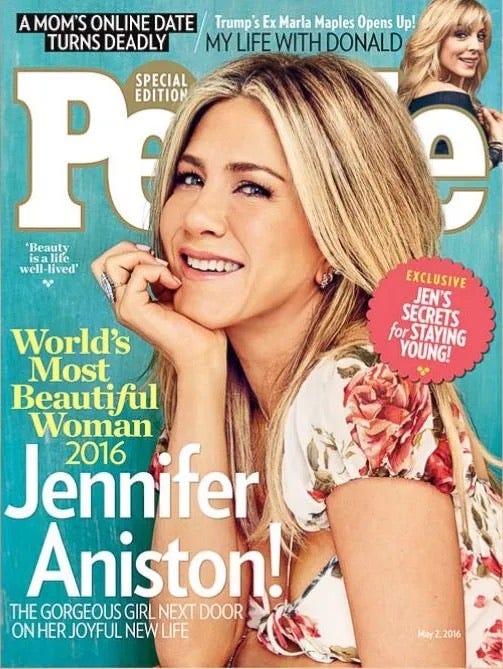

I used to love AOL News and People Magazine. In the 1990s and 2000s, both these rags served their purpose. I could access the 100 Most Beautiful People, get my weekly update on Brangelina, and witness the cultural divide that still upheld Jennifer Aniston as the most beautiful woman. The girl’s girl. A solid 10 in Boston. Meanwhile, Angelina Jolie was seen as the big lip dragon woman. For some reason, this cultural schism always felt racial, even though they were both white. Strange how anti- blackness works. One played the pick me of the century, Rachel on Friends. The other played my personal favorite, Lisa in Girl, Interrupted.

I will always be an Angelina girl. It’s the trauma in me.

These glossy rags and their digital iterations like TMZ have their purpose: to cash in and build vacant myths of spectacle. From the president of the United States to the stripper ex-fiancée of an NBA player, it all serves the same function. A conduit of attention, designed to be translated into profit. Also, a bit of a blackmail ring, depending on who you ask. Harvey Levin has built an entire business model around holding the wealthy and famous accountable to whoever can afford his services.

Outside of Levin, there are entire PR companies built solely to smear and alter public perception, running like clockwork on USA Today, Yahoo News, or whatever once-legitimate outlet that has collapsed into a click farm. My personal favorite is Forbes. The illusion of a prestige arena, where half the "journalists" are operating offshore out of call centers in Kolkata.

There is nothing wrong with a Bengali-run American news site. The question is why a worker making fifty cents an hour would care about the journalistic integrity of an article about Barack Obama. They wouldn’t.

It has already been proven that digital media and magazines do not have money. With direct to consumer advertising through social media, there is no reason to pay Vanity Fair fifty thousand dollars for an ad placement when you can pay an influencer with real-time engagement and specified metrics a fraction of that to make a viral video.

Where does that leave art journalism?

It leaves it where it has been festering for a while. A self-righteous, glorified Page Six. A place where “failed” artists can pivot, trade in their brushes for bylines, and build power among their peers. A place in the pockets of the top one percent of galleries, artists, and dealers who use it as their own personal rocket launcher against opposition. After a lawsuit. As a device in a smear campaign. As a tool for a hostile takeover. Or whatever else these weirdos cook up in their free time.

I have been targeted by the art press myself. Nate Freeman, who now works at Vanity Fair stuffing his nose up the rich and famous. Ann Binlot from Document Journal, who runs on some kind of BIPOC “model minority” oppression complex, simmering over the black girl who got more attention from weird men she wanted recognition from. And the weirdo who runs Cultbytes.

None of them have journalistic integrity. But that is not surprising, because art journalism itself does not have journalistic integrity. It is a glorified blog. A place where a critic’s pick on Artforum might earn you fifty dollars, if you are lucky. These supposed journalists decide what to write about based on the perks they receive. It is not just that journalists are being bought and sold. They are openly advocating to be used by the rich and powerful.

Jay Penske, son of Roger Penske and head of Penske Media Corporation, owns nearly all major entertainment media outside of social media. His most impressive position is probably as the largest shareholder in Vox Media. The acquisition of Art in America, ArtNews, and Artforum might seem impressive until you realize how out of sync those publications are with the rest of the company’s portfolio. Not because of their content, but because of the basic numbers, the ability to inflate impressions dramatically, launder prestige for the art world, and contribute to an oversaturated market that makes the truth harder to see.

Art journalists are not even pressured through old fashioned intimidation anymore. They are overwhelmed with impressions, with access, with the promise of proximity.

Artnet’s Wet Paint, a weekly column run by Annie Armstrong, reads like the ketamine addicted version of the corpse of Vice Magazine, so desperate to maintain a shred of counterculture lore that even neo-fascism is openly used and embraced. Dealers like Matthew Brown are mentioned, though no one really cares about the art dealer beyond the fact that his grandfather is an oil baron and he is married to Marlene Zwirner( David Zwirner daughter). Framing them as a "power couple" has no bite. It is not aspirational. It is formulaic.

When Johnny Depp and Kate Moss were rolling around in bed in 1994, it was sex appeal. This is not that. There is no sex appeal in that marriage. Maybe money. The kind of money any rich kid can access by opening a gallery. But there is nothing cool about it.

ArtNews does not write against any of its advertising clients. The Armory Show withheld two thousand dollars from me, and ArtNews killed the story. Maybe because Frieze, who recently acquired a stake in the Armory, is a major sponsor. Maybe because two thousand dollars is a small price to pay to keep the machine running.

All the articles about "progress" are fluff pieces meant to fill space. The only slightly biting story recently is the coverage of Kehinde Wiley’s sexual assault allegations, which have been an open secret for a long time. And even then, people barely care. Most people do not care.

I was once sexually assaulted in front of senior Pace Gallery directors in Venice and told to be quiet by a well-known European gallerist and collector. Where are the allegations against the powerful, wealthy white men who sell art to the people listed in Jeffrey Epstein’s black book?

Black women cannot be raped in the white Anglo-Saxon psyche

Crickets. We will not get that story in ArtNews, Artnet, Art in America, or Artforum.

Instead, we will get the stories about a nonwhite person owing money. A woman being indicted in criminal court. The “other” usual targets, taking the fall for an industry that exists to protect and fuel abusive white men.

If art journalists actually did their jobs, they would uncover multiple abuse rings connected to major art collectors. They would uncover the culture of fascism and white supremacy that runs through the foundations of the industry. But it is not in their interest. Their interest is to propagandize. To act as foot soldiers for the wealthy.

It can be argued that the death of art criticism is directly linked to the rise of art journalism. Critics cannot say what they want. Editors are more concerned with who attended the afterparty than what was on the walls. Prolific thinkers end up seeking refuge in art rags, hoping for legitimacy from an industry that cannot even pay them properly. Some of them have been working adjunct or underpaid at the same universities for twenty years without ever securing tenure.

The only ones who benefit are the galleries. They can buy ad space in the publications and, in exchange, ensure that their shows are reviewed heavily enough to solidify their artists as "canonical." The museum curator is not a critical mind anymore. They are just a stop on the conveyor belt that appreciates the stock portfolio of billionaires.

Now ArtNews' Senior Editor and Editor-at-Large, Alex Greenberger, who I have written about before, is commenting on the fact that four museum exhibitions currently feature artists represented by Hauser and Wirth. All four artists happen to be black.

Sometimes I wish Alex would just say the quiet part out loud, instead of pretending the crisis lies in bad figurative painting or tiptoeing around the whole apparatus of Hauser and Wirth.

Rashid Johnson’s show at the Guggenheim looks lackluster. It feels like an exaggerated performance of academic emptiness, warped by capitalism and self-importance. It is similar to the Beyoncé country album—necessary in theory, but not rigorous in execution, because both are already wealthy, famous, and insulated. I have the same criticism for Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis—great artists often plateau when comfort sets in.

In Interview Magazine, Johnson tells Jeremy O’Harris that he is not the voice of working-class black people. That much is obvious. He lives in East Hampton. It is an easy out, a preemptive move to distance himself from any serious critique of his premature retrospective at the Guggenheim.

The distance from the working class, especially in a political moment sliding into open fascism, feels absurd. But Rashid Johnson is exactly the kind of black artist Greenberger and the mostly white boards of museums want. black, but not too black. A digestible figure. A black nihilist with a sprinkle of black neoliberalism.

This is the real culprit Greenberger dances around in his half-hearted critique, trying to assemble an obvious truth: museums do not have money, and galleries now fund them. It is not surprising. Rashid Johnson is also the 2020s version of Maurizio Cattelan—part artist, part shadowy tastemaker. A figure with far more influence than most people are willing to admit.

Greenberger, like most art journalists, is stuck walking a tightrope of millennial frustration, cowardly half-critiques, and an addiction to Kafkaesque aesthetics.

The art world does not want criticism. It wants content. It wants the appearance of friction without the reality of consequence. The journalists do not want the truth. They want access. They want survival. The galleries do not want culture. They want assets.

There is no way to write from inside the machine without naming the machine for what it is: a mechanism of power, laundering itself through aesthetics, through diversity initiatives, through spectacle.

The truth is boring.

The corruption is obvious.

The decline is irreversible.

All that is left is to decide whether you are going to keep pretending not to see it.