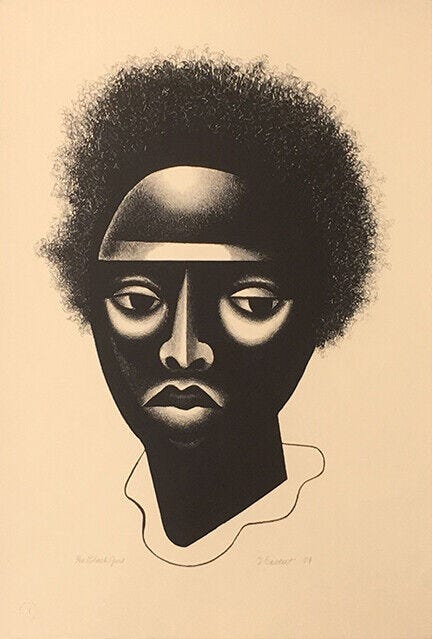

Elizabeth Catlett, Black Girl, 1969.

With the elusive proclamations of anti-identity art and lackluster attitudes toward auction-breaking Black figurative painters in post-Trumpian society, the most honest deconstructive position is: why is bad Black art elevated? This question is akin to asking why Black women are often deemed unattractive—a perception shaped by the indoctrination of Eurocentrism. Within our paradigm of beauty and desire, it explicitly confirms that anyone who embodies and pivots toward European standards will be deemed attractive in a Westernized European country. This paradox also informs the fetishization and othering of Black women, shifting the oppressed into a delicacy. Regardless, it affirms the stripping of their humanity for not embodying the presumptive status of a femme-identified person.

This eugenics-driven propaganda sustains capitalist juggernauts like the fashion industry, where metrics of desire are quantified and upheld by the ruling class as a marker of wealth and, anecdotally, survival. To confirm what “bad Black art” is, one must interrogate the validity of the position of “good art”—or, more aggressively, reduce it to “white art.” Pure art. The neutrality of the European canon is not just a passive position but an intentional hierarchical impulse to strip any Indigenous or African influences in order to uplift the nature of European aesthetics. Like rock ‘n’ roll, which has shed decades of its origin stories to accommodate the preferences of white America, the belief that rock ‘n’ roll was always white allows for a cultural event unburdened by the legacy of colonialism and pillaging. It is the societal version of “kid gloves” to protect white fragility.

Art relies on myth, and the sexier the myth, the more likely you will enter the canon. Dash Snow and Basquiat have more in common beyond premature death. Both exemplified the era of downtown New York in their primes. The mythology of the East Village and Lower East Side has its own seminal history, comparable to Hollywood. A grittier and often more authentic legacy—a city where art is born. The seduction and romanticism of this bohemian center provided the backdrop to figures like Blondie, Allen Ginsburg, Sonic Youth, and writers like Ishmael Reed. The lore of these musicians and cultural figures has been weighed and used as determining factors in the appraisal of art objects. The power of NYC’s downtown culture in the late twentieth century is constantly in a loop, ornamenting neighborhoods like Dimes Square and creating a Disney World of counterculture and dissent. Yet in the age of social media and cultural decay, marketing strategies and publicists outweigh the organic communities and discourse that defined seminal eras of art and culture. The radical or political stances of anti-authoritarianism once represented in these movements have been hollowed out. They now function solely as an aesthetic to amass a cult following with no substance beyond giving a “look.” This is the state of high, good, contemporary art: a vein of chronicled European art canon, the mysticism of counterculture, and the approval of the “right” galleries, which tend to promote this mythology of exclusivity and rigor.

This dynamic of exclusion and commodification has deep historical roots. Adrian Piper critiques this dynamic with precision in her essay The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artists (1990). She recounts Rosalind Krauss’ 1983 claim at the NEA symposium that no unrecognized African-American artists of quality existed because, according to Krauss, they would already be known to her. Similarly, Roberta Smith’s 1989 statement dismissed Black art as inherently derivative, further cementing systemic exclusion (Piper, Adrian. “The Triple Negation of Colored Women Artists,” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 17, No. 4, 1991, pp. 759–780).

Despite these attitudes softening publicly in recent years, their underlying logic remains. Critics like Smith now champion Black artists in galleries like David Zwirner, masking their earlier biases. Today, Black art is treated as a trinket of progress—a symbol of racial equity that still upholds white dominance in ownership and access. This neocolonialist strategy, masked as upward mobility, reduces radical traditions to easily consumable objects like paintings of blackface. These works, auctioned for generational wealth siphoned from Black communities, perpetuate a cycle of exploitation disguised as progress.

Art critics like Dean Kissick and Alex Greenberger argue that what is dismissed as “bad Black art” reflects an art system falling prey to woke politics, draped in a coexist flag. This is epitomized by Kehinde Wiley’s easily digestible portraits of homeless Black youth rendered in a neoclassical style, often displayed in European estates or Newport mansions owned by fetishistic heiresses seeking escape from the mundanity of their wealth. Wiley’s advanced techniques, resembling collegiate entrance exams, secure his place as one of the most recognizable Black painters, yet his reliance on the European art canon underscores his comfort within these frameworks.

This reliance on European frameworks creates a template for Black artists to navigate a system designed to commodify their work while diluting its radical potential. Younger artists like Aria Dean, Noah Davis, and Alvaro Barrington illustrate this dynamic, rising in a more accommodating yet surveilled market shaped by Hollywood-style projections of capital gain. Their careers often echo the paths of Kerry James Marshall, Adrian Piper, and David Hammons, whose works transcended market constraints to define their own narratives. Dean’s practice mirrors Piper’s relentless philosophical inquiries into identity and representation, while Davis employs Marshall’s rich palette and blends realism with surrealism to explore the intricacies of Black domestic life. And, anticlimactically, the death of Davis is what also cements him into this tragic trajectory in a late capitalist world, where his passing amplifies his marketability and mythos.

Barrington’s trajectory, however, aligns with Hammons’ mystique, though his performative myth is collaboratively constructed by the galleries that represent him. Unlike Hammons—whose rebellious lore, despite its problematic “magical negro” trope, emerged from acts of defiance—Barrington’s narrative is shaped by market strategies that commodify mystique itself. This reveals the art world’s ability to turn subversion into spectacle, repackaging rebellion as a product while upholding the systems it claims to critique.

Relational necromancy—the act of commodifying and exploiting the dead or elderly—is not limited to celebrated galleries. It can be found in local art gallery hybrids that showcase Basquiat impersonators with free-form locks, aspiring to genius while unknowingly serving as myths packaged to benefit the ruling class. This dynamic is evident in Hilton Als’ 2022 Toni Morrison exhibition at David Zwirner, where Morrison’s radical legacy was reframed to fit within the confines of an elite, white-dominated gallery space. Morrison, who worked as an editor at Random House and taught at Princeton, was a product of hierarchical institutions, yet her work remained deeply accessible and rooted in Black liberation. The artist list, featuring names with staggering auction results, reflects the transactional nature of the exhibition, prioritizing capital appraisal over genuine engagement with Morrison’s legacy. Als, now a hollowed-out figure of Ivy League prestige, serves as a stamp of approval for the gallery system’s anti-Black, white elitist agenda. David Zwirner neutralizes Morrison’s radicalism, reducing her contributions to consumable aesthetics for wealthy patrons rather than an enduring critique of systemic inequities. This epitomizes relational necromancy: resurrecting the revolutionary to serve the very systems they opposed.

This collusion of the vacuous Black intellectual plays an integral role in continuing the legacy of white dominance over Black cultural production. We now find a generation of aspiring Black cultural producers more invested in cultivating a respectable image than in innovation or challenging the status quo. Even those who claim rebellion often lean into the racially charged notion of not being considered a ‘Black artist’ but simply an ‘artist.’ This framing proposes a universal neutrality that European artists are granted, yet it is a fictitious and distorted claim. All art is rooted in experience and shaped by identity—whether explicit or implicit—making neutrality an impossibility.

Many Black art graduates, having already been indoctrinated into uplifting either European art or Black art filtered through a European canonical framework, end up striving for this same so-called neutrality. This is an issue of assimilation, which ultimately perpetuates what bell hooks termed ‘Black schizophrenia’—the inability to access true ideological freedom while relying on the tools of the oppressor.

The deliberate elevation of “bad Black art” is not a glitch in the system; it is the system. By rewarding art that conforms to Eurocentric ideals or flattens Black radical traditions into easily consumable aesthetics, the art world ensures its continued domination over Black cultural production. It is not enough to expose this collusion—Black artists, intellectuals, and audiences must confront the structures that demand assimilation, silence rebellion, and reduce innovation to a market trend.

What does it mean to create art that refuses? Art that denies the galleries, critics, and institutions their transactional expectations, their sanitized notions of Blackness, their hunger for profit disguised as progress? The power of Black art has never been in its ability to appease but in its capacity to disrupt, to fracture the myth of neutrality, and to demand a reckoning. This is the challenge: to unlearn the tools of the oppressor and to build something ungovernable—art that doesn’t negotiate its place within the white-dominated systems of appraisal but abolishes them entirely.

The euro system insists non white non straight non male artists carry a double load. Always. With an exemption for white gay men. So it’s point of anxiety at the entrance and a sort of people pleasing relationship is built immediately. Radicalism is tempered unless the notes are set a fire. But never big enough to take down the system. I wonder did Hans H ever make a painting? Is the painting a Trojan horse? Can it be? Love your piece.

I’d like to see black people break out of this dynamic but I can’t say I’m optimistic about it.